If

you know me, or if you’ve followed this blog for a while, you might have

already guessed that I would be following the events in Ukraine closely. I

haven’t blogged about it any, as I am not an expert on Ukraine, and as there are many experts and folks on the ground sharing their views and stories. (However, as

there are many talking heads out there presenting themselves as ‘experts’ who

in fact have no clue, I’d probably fit right in, and maybe even do a better job; sigh.) However, I ran across

something last night that I really wanted to share. That ‘something’ was an

article, published in 2004 in volume 27 of the Ethnic and Racial Studies

journal, written by Greta Uehling, and entitled The first independent Ukrainian census in Crimea: Myths, miscoding, and

missed opportunities. It discusses the 2001 Ukrainian census, with a focus

on the Crimean peninsula. It’s not the most recent of articles, but it provided

some really interesting insight to the current situation in Crimea.

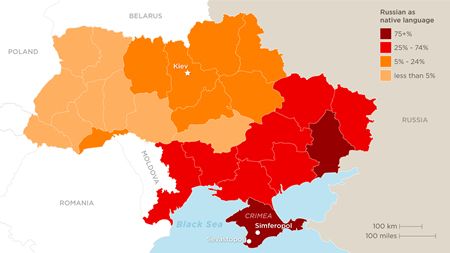

Over

the past few weeks, I have seen an inordinate amount of maps, such as this one

from CNN:

From what I read, however, it seems that the facts pertaining to nationality and language in Crimea might not be as clear-cut as presented in the mainstream media. Now,

granted, the article I'm referring to is on the 2001 census, not on the more recent

2011 census; however, if any of the flaws present in the 2001 census remained

in 2011, then the lines on the map might not be anywhere near as distinct as

the ‘experts’ on the various news shows would like us to believe. As I

mentioned, the article in question focused on the Crimea. Based on the

observations and interviews conducted by Uehling, it seems that there were a

lot of biases among the census-takers themselves, and these biases directly

affected the manner in which facts pertaining to native language and

nationality were reported.

The

article stated that that when individuals were asked what their native language

was, "if a

person responded 'Russian' or 'Crimean Tatar' it was simply written as stated.

If, on the other hand, the answer was Ukrainian language, the census takers

were instructed to ask for clarification. This created a certain pressure for

respondents in Crimea to scale back their level of Ukrainian” (p. 158).

In

addition to asking about individuals’ native language, census-takers were

instructed to ascertain each individual’s nationality. “[O]ne census-taker

automatically identified several respondents as Russian, based on the fact that

they said Russian was their native language…. [because] it had been ‘apparent’

to her that they were Russian” (p. 156). During my (albeit short) time in

Ukraine, I met many ‘ethnically Ukrainian’ people who spoke Russian as their

first language, which makes this kind of assumption seem rather absurd.

Additionally, people were allowed to report on other individuals, such as

fellow dorm residents and flatmates, whose actual first language and

nationality might not have been known to them.

Another

problem was that mixed nationalities were not an option - so if someone had,

say, a Ukrainian mother and a Russian father, there was no accurate option to

explain their nationality. In Crimea, apparently, the census-takers tended to

write 'Russian' for nationality in such circumstances, whereas in western

Ukraine census-takers tended to write Ukrainian in such circumstances. One

example included in the article stated, “[W]hen a woman did not know what to

say about her son’s nationality, the census-taker suggested that, ‘Since

nationality is determined by the father in Russia and by the mother in Ukraine,

we will write down Russian.” Such ‘logic’ is rather mind-boggling.

Like

I said, this article is based on the 2001 census, not the most recent one.

However, it should give you something to keep in mind when you see all those

maps of a ‘divided’ Ukraine.

![international [cat] lady of mystery](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgnPJiUgfmMHEUcIPKDuSiTQFpnXgSofemne4WBX0VfEv-Bym8HdPHiD-iC2mNCJQog2tvPXKao_9vpRJG_vl4Yfi0ZTX_p3YpHLCie0rUHAJLgwcAb-Otj7hzc-_UkSI-yRNlpG45z8Wo/s1600/newblogtop2014b.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment